Towards the end of 2024 Microsoft announced new configuration opportunity for Azure Private DNS zones called fallback to Internet. I think that it was announced more or less right after the 2024 Microsoft Ignite event. This functionality is, at the point of writing this blog post still in preview so proceed with caution 😼

I’ve started working with it shortly after it was released, and I would like to share some thoughts and use cases here where utilizing this functionality can make sense, as well as demonstrate how you can implement it yourself.

How does it work?

Fallback to Internet for private DNS zones can prove very handy when you’re utilizing private endpoints, especially in a multi-region scenario. Let’s take a look at a typical example workflow for creating a private endpoint for an Azure Key Vault (the same workflow is applicable for any other Azure resource that supports private endpoints):

- Create a private DNS zone that will contain records mapping every Key Vault behind private endpoint to its private IP address. Normally the private DNS zone for Azure Key Vault is

privatelink.vaultcore.azure.net. - Create a virtual network link between the private DNS zone and a virtual network that will provision private IP addresses for the respective private endpoints.

- Create a private endpoint in the respective virtual network subnet and connect it to the Azure Key Vault resource.

- Disable public network access on the respective Azure Key Vault.

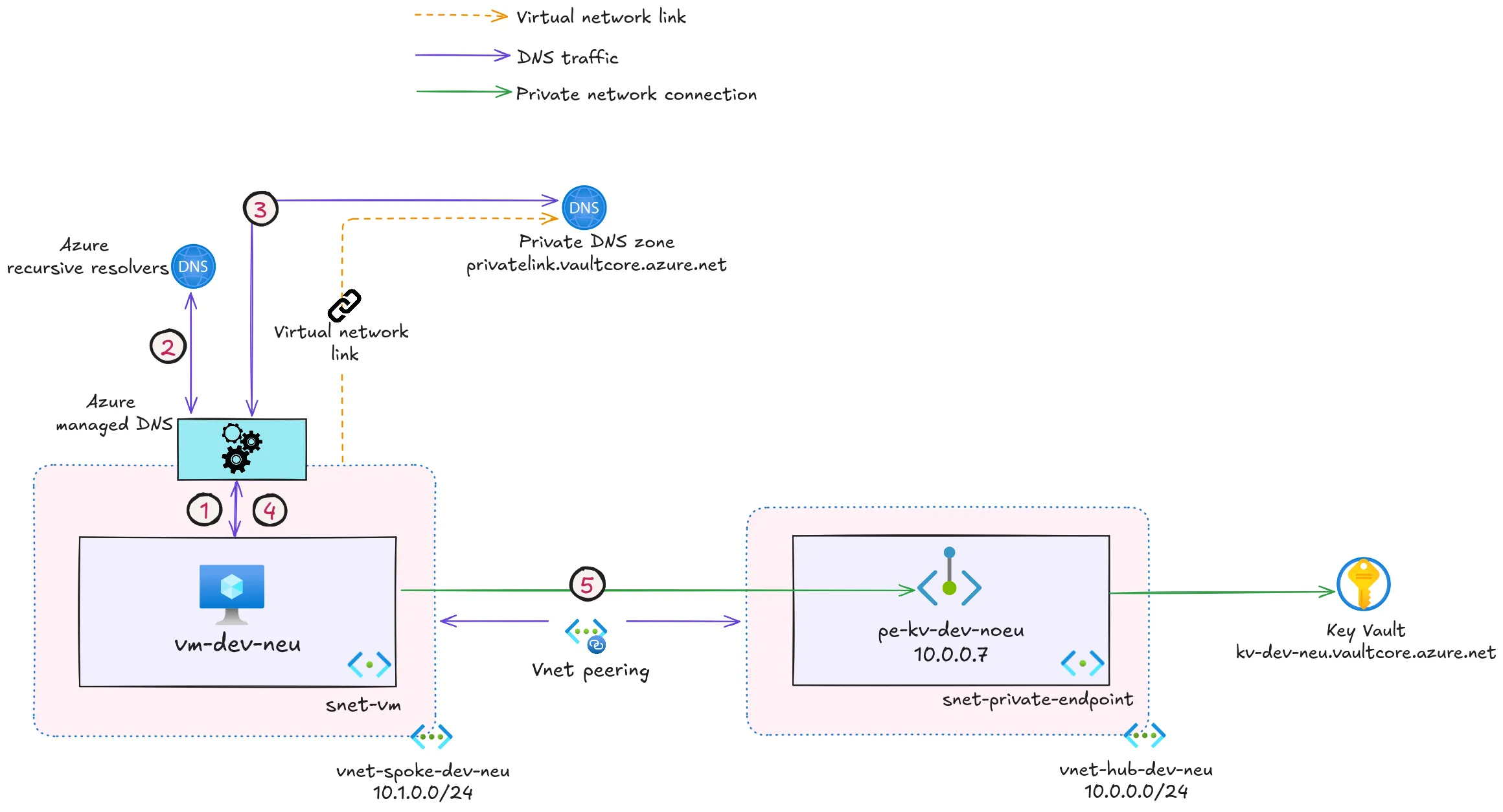

Once private endpoint is configured and enabled, DNS resolution workflow for the requests that are attempting to access the key vault will look something like the image below. Here I’ve chosen to illustrate how it will look like if you have a hub-spoke network topology, but you can check how the same flow will look like with a single virtual network in Microsoft documentation: Azure Private Endpoint DNS integration

Let’s go through it step by step. DNS query for the key vault kv-dev-neu.vaultcore.azure.net first reaches Azure-managed DNS service (1), where it’s being resolved via Azure-managed recursive resolvers as a CNAME to the key vault’s private endpoint: kv-dev-neu.privatelink.vaultcore.azure.net (2).

Next, the endpoint’s fully qualified domain name (FQDN) is being resolved to a private IP as registered in the domain records in the private DNS zone for Azure Key Vault: privatelink.vaultcore.azure.net, which we created in step 1 in the beginning of this section.

Resolved private IP address for the private endpoint is returned back to the Azure-managed DNS service: 10.0.0.7 (3).

From there the resolved private IP address is sent further to the caller, which in our example is a virtual machine: vm-dev-neu (4).

From that point onwards the connection from the virtual machine to the respective key vault is happening over the private endpoint’s private IP address (5).

This example workflow is not exhaustive of course. Depending on what resources you would like to put behind private endpoints and what kind of architecture you have in place you may need to do additional steps, like creating virtual network peerings, setting up private DNS resolvers, virtual network gateway for a hybrid cloud scenario, etc. Private endpoint implementation for different scenarios can be a dedicated blog post in itself 😅

The main point here is that once all the above steps are done and the Azure Key Vault is only accessible through a private endpoint and its private IP address, all of the requests that are attempting to reach the key vault will only be resolvable by the respective private DNS zone.

But, what if you have a multi-region setup where both regions are using private DNS zones and are not interconnected, and a virtual machine from one region needs access to a specific Key Vault that is behind private endpoint in another region? 🤔

Originally that wouldn’t be easy to achieve out of the box and would require you to make larger infrastructure changes and potentially increase complexity by introducing cross-regional virtual network peering for instance. But what if you don’t want (or can’t, for example due to overlapping IP ranges) implement full-blown interconnected multi-regional setup for private endpoints with virtual network peerings? Maybe instead you would like to just whitelist the IP of that virtual machine or the NAT Gateway IP for traffic coming from that region on the Key Vault’s firewall level?

That’s where the fallback to internet functionality comes into picture! 🎉 By enabling this configuration setting, you can support scenarios where access via private endpoint isn’t possible, but the resource behind private endpoint can still be reached over the internet by the whitelisted IP addresses, while all the other traffic still flows through the private endpoint.

Scenario that was mentioned above is similar to the one I faced. In my use case there was a multi-regional setup (including private endpoints) where every region operated in isolation, but there was a specific, common resource in one of the regions that needed access to some of the resources behind the private endpoints in a different region. An option there would’ve been to introduce cross-regional virtual network peering, but it wasn’t applicable in that use case due to security restrictions and the undesirable additional complexity that this change could introduce. Utilizing the fallback to internet functionality actually made it pretty straightforward to resolve this challenge and simply whitelist the IP that needed access to the resource behind the private endpoint, while still enforcing resolution of all the other traffic to the endpoint’s private IP address.

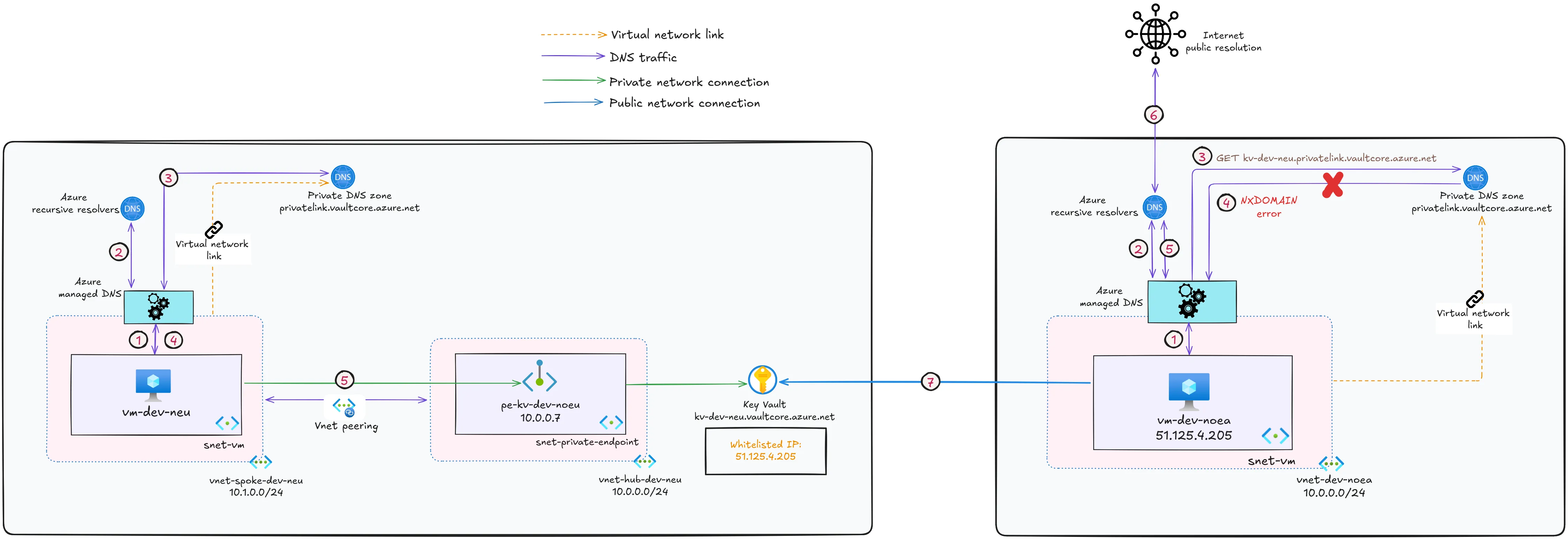

To illustrate the new DNS resolution flow, let’s build upon the earlier example.

Let’s say that we have a virtual machine in Norway East region that is in the virtual network that is linked to the private DNS zone for key vault in Norway East region. This VM also needs access to our key vault in North Europe that is now behind a private endpoint that is linked to the private DNS zone for key vaults in North Europe region.

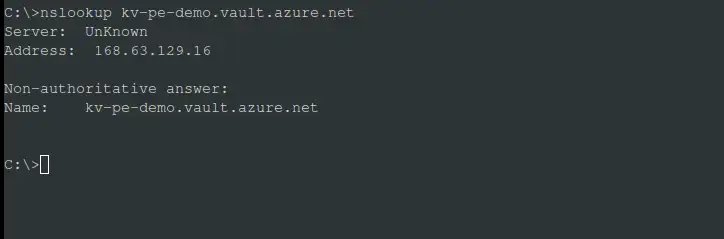

With the fallback to internet setting disabled, DNS resolution will come back empty, as shown below, since DNS resolution will start in the private DNS zone in Norway East, but that private DNS zone doesn’t have any mapping for the key vault’s private endpoint since it resides in North Europe.

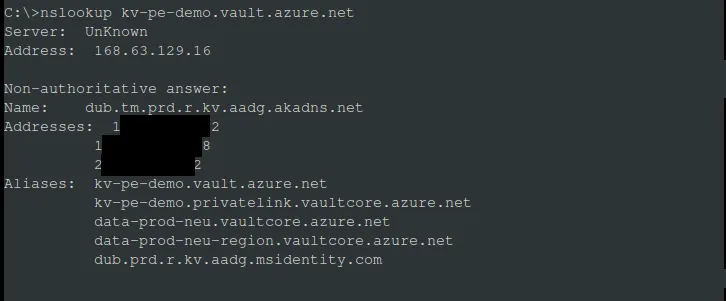

If we enable the fallback to internet on the private DNS zone in Norway East, after the initial DNS resolution via the private DNS zone is unsuccessful the DNS resolver will use the public DNS resolution based on the resource’s public endpoint qualified name (QNAME).

To round up our example, the updated DNS resolution flow can be visualized like this:

How to enable it?

Configuration option for this functionality is available in API version 2024-06-01 or higher. At the point of writing this blog post it was unfortunately not available in the Azure Verified Module for private DNS zone or in the AzureRM provider for Terraform, but there are a few options on how you can configure it anyway😸

This functionality can be configured during creation of the virtual network link in the private DNS zone or by editing existing virtual network link.

Bicep

Fallback to internet can be configured on the virtual network resource by setting resolutionPolicy value to NxDomainRedirect, as shown in the code snippet below.

// virtual-network-link.bicep

param dnsZoneName string

param tags object

param vnetId string

resource dnsZone 'Microsoft.Network/privateDnsZones@2024-06-01' existing = {

name: dnsZoneName

}

resource vnetLink 'Microsoft.Network/privateDnsZones/virtualNetworkLinks@2024-06-01' = {

parent: dnsZone

name: '${dnsZone.name}-vnetlink'

location: 'global'

tags: resourceTags

properties: {

registrationEnabled: false

resolutionPolicy: 'NxDomainRedirect' // <-- enable fallback to Internet

virtualNetwork: {

id: vnetId

}

}

}

Terraform

Configuration for fallback to internet is unfortunately not yet available in the AzureRM provider for Terraform, but you should be able to configure it with AzAPI provider like this:

// main-virtual-network-link.tf

resource "azapi_resource" "vnet_link" {

type = "Microsoft.Network/privateDnsZones/virtualNetworkLinks@2024-06-01"

parent_id = "<private_dns_zone_resource_id>"

name = "<virtual_network_link_name>"

location = "global"

body = {

properties = {

registrationEnabled = true

resolutionPolicy = "NxDomainRedirect" // <-- enable fallback to Internet

virtualNetwork = {

id = "<virtual_network_resource_id>"

}

}

}

}

Azure CLI

az network private-dns link vnet create --name <virtual_network_link_name> \

--resource-group <private_dns_zonre_resource_group_name> --virtual-network <virtual_network_name> \

--zone-name <private_dns_zone_name> --registration-enabled False --resolution-policy NxDomainRedirect

az network private-dns link vnet update --name <virtual_network_link_name> \

--resource-group <private_dns_zonre_resource_group_name> --zone-name <private_dns_zone_name> \

--resolution-policy NxDomainRedirect

You can also go the classic way and configure it via Azure portal (also on existing private DNS zones) - check out the first linked article in the session below for more information on how to do that!

Additional resources

Below you may find a few additional resources to learn more about the topic of this blog post:

- Fallback to internet for Azure Private DNS zones (Preview)

- Overview of private endpoint DNS zone values for different Azure resources

- Azure Private Endpoint DNS integration

- Azure CLI documentation for managing virtual network links for private DNS zones: az network private-dns link vnet

- What is NXDOMAIN? and What is a Recursive DNS server?

That’s it from me this time, thanks for checking in! If this article was helpful, I’d love to hear about it! You can reach out to me on LinkedIn, GitHub or BlueSky 😊

Stay secure, stay safe. Till we connect again!😼